Development and Implementation of a Digital Skills Learning Ecosystem via the "Manabiai" Program―Realizing smart inclusion through multi-generational mutual support―

Yasuyuki Taki

Director, Smart Aging Research Center (SARC), Tohoku University

Professor, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer (IDAC), Tohoku University

Kentaro Oba, Michio Takahashi, Akari Uno, Keishi Soga

Smart Aging Research Center (SARC), Tohoku University

Project Synopsis

Although the government is working to realize a society in which everyone can enjoy the benefits of digitalization, there is still a digital divide among older adults due to various barriers such as anxiety about digitalization as well as the technology itself.1 Local governments and private companies around Japan are offering smartphone classes and IT courses to older adults, but their effectiveness and uptake have reportedly been limited. In order to overcome these limitations, our project aimed to develop and implement a digital skills learning ecosystem in which older adults can enjoy learning while experiencing social connections based on their actual needs.

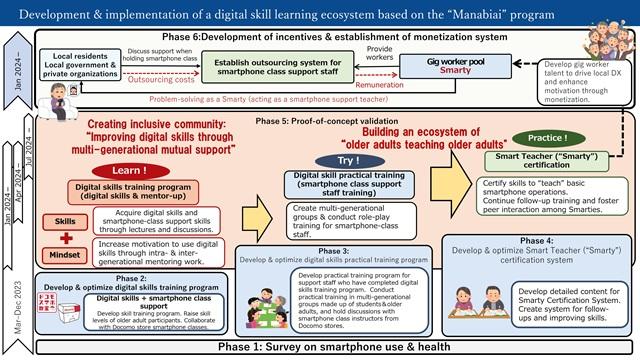

The project comprised six phases (Fig. 1). In Phase 1, we conducted a survey of 10,000 older adults regarding their smartphone use and health. In Phases 2 through 4, we assigned university students as support staff and developed a program that enabled participants to learn basic smartphone skills through multi-generational "manabiai" (literally "learning together"). In Phase 5, we performed a validation study to determine whether older adults with certified skills ("Smart Teacher" or "Smarty") could act as teachers, and in Phase 6, we attempted to build a monetization system to support Smarty activities.

This project was implemented as the "SENdai Smart Inclusion (SENSIN) Project"--a joint industry-government-academia initiative led by NTT Communications Corporation (now NTT DOCOMO BUSINESS, Inc.), Sendai City, and Tohoku University with the cooperation of Sendai's citizens.

Project Outcomes

1. Surveys on smartphone use and health (Phase 1)

In our survey questionnaire asking older adults who they asked for help when unsure how to operate a smartphone, the majority of respondents chose "I don't ask anyone for help (I solve the problem by myself)" (39.5%), followed by "the customer counter at the mobile phone store" (12.4%), "non-cohabiting family members" (10.9%), "cohabiting spouse" (10.7%), and "friends and acquaintances" (<10%). These responses suggest that instances of "older adults teaching older adults" are very rare, and that this hitherto rare practice of older adults teaching each other is a promising method that presents new possibilities for bridging the digital divide. Moreover, our survey on duration of smartphone use and perceived happiness showed a significant positive correlation between these two variables (P<0.001). Given the finding of a previous study that older adults who used the internet to communicate with family and friends had a high level of perceived happiness,2 the results of our survey also suggest that the participants used smartphones as a tool for social connection, and that this connection may have manifested as the correlation with perceived happiness.

2. Development of the "Manabiai" program (Phases 2-4)

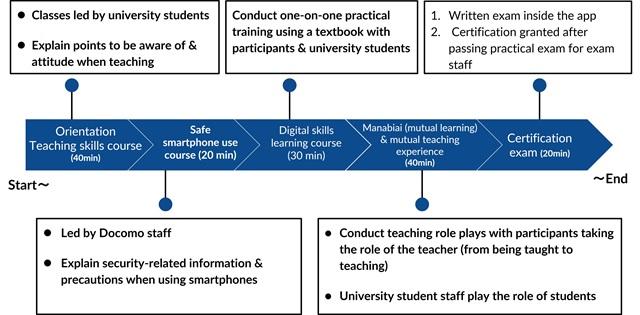

In this project we developed a program for older adults aged ≥65 years to learn basic smartphone skills and teaching skills through intergenerational learning3 (Fig. 2). The university students acting as program staff worked one-on-one with the older adult participants using an original textbook to review basic smartphone skills (in which participants selected one of six skills comprising making calls, using the camera, sending emails, accessing the internet, using maps, and making cashless payments). Through role-playing, in which the older adult participants acted as teachers and the staff as students, the participants were encouraged to shift from being taught to teaching. The older adult participants who passed the written and practical exams for each smartphone skill were then certified as Smart Teachers ("Smarties"), and participants could take part in the program multiple times to acquire each skill. The table below shows the project's five KPIs and their status, including the number of certified Smarties.

KPIs and their Status

The table below shows the KPIs and their current status.

| KPI | Participants | Progress |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Program enrollment target of 6,000 older adults | 6477 | 108% |

| 2. Total of 120 trained older adult participants certified as Smart Teachers ("Smarties") | 272 | 227% |

| 3. Total of ≥1,200 older adult participants trained by Smarties | 1,512 | 124% |

| 4. Total of 120 smarties (100%) who felt confident providing digital skills training to older adult participants | 292 | 235% |

| 5. Total of 960 older adult participants (80%) who felt confident using digital tools on their own after receiving training by Smarties | 1,253 | 126% |

1. Program enrollment target of 6,000 older adults

In collaboration with NTT Communications and NTT Docomo, we enrolled older adults in our program who had learned basic smartphone operations after taking part in a free smartphone class held at Docomo mobile phone stores in Sendai City. We distributed "Manabiai" program notifications and original textbooks to the participants. While the target sample size was set at 6,000 older adults, the actual number of enrolled participants reached 6,477.

2. Total of 120 trained older adult participants certified as Smart Teachers ("Smarties")

A total of 27 Tohoku University students participated as support staff in a total of 33 "Manabiai" programs held at civic centers in Sendai City. Through these programs, a total of 272 older adult participants were certified as Smarties, far exceeding the initial target of 120.

3. Total of ≥1200 older adult participants trained by Smarties

In this project, the term "Smarty experience" was used to describe the activity of teaching certified skills to family and friends, and a system was established whereby Smarties reported the content and number of participants they taught using a dedicated app. The reported number of participants taught was visually represented in the app and novelty items were awarded to the Smarties in an effort to maintain their motivation. The reported number of participants taught reached 1,512, far exceeding the initial target of 1,200.

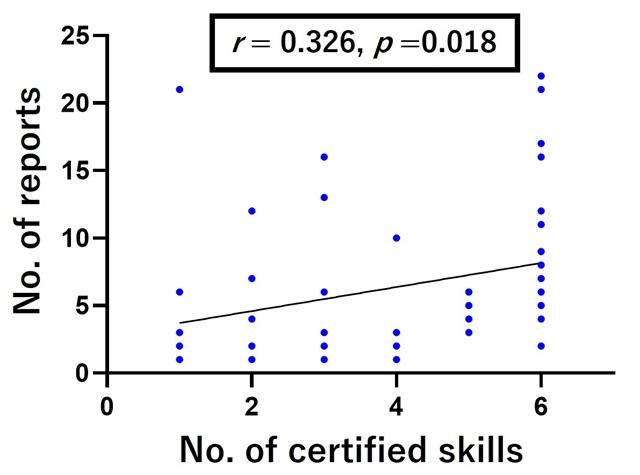

We also identified a significant positive correlation between the number of certified skills (up to six) and the number of Smarty experiences (Fig. 3), indicating that providing opportunities for the older adults to continue studying smartphone operating skills may contribute to knowledge dissemination.

4. 100% of Smarties reporting that they felt confident providing digital skills training to older adult participants

When reporting on their Smarty experiences, we requested that Smarties also report on their confidence in teaching the other older adult participants. As a result, a total of 292 Smarties reported that they felt confident in their teaching, far exceeding the initial target of 120.

5. 80% of all older adult participants reporting that they felt confident using digital tools after the Smarty training

When reporting on their Smarty experiences, we requested that Smarties also report on the status of the older adult participants they taught. As a result, the Smarties reported that 1,253 of the older adult participants appeared to be confident using digital tools after the training, far exceeding the initial target of 960.

Initiatives toward Social Implementation (Phases 5 and 6)

We performed a validation test to determine whether Smarties certified by the project could serve as support staff in smartphone classes conducted by other organizations not involved in the project. Our findings demonstrated the feasibility of a monetization system in which organizations contracted by Sendai City's Community Comprehensive Support Centers to conduct the smartphone classes will hire and remunerate Smarties. The "older adults teaching older adults" model was also well received by the participants, who found it easier to ask questions to their peers than to be taught by younger generations, resulting in a friendly and relaxed atmosphere within the classroom. Although testing during the project period was limited to the validation of a monetization system, if a sustainable support staff training and dispatch organization could be established, then it may be possible to realize social implementation by meeting the need for smartphone classes among older adults.

Future Prospects

This project demonstrated that the "older adults teaching older adults" model may be effective in bridging the digital divide. In order to continue developing this highly public activity in the future, we are considering establishing a non-profit organization and expanding the number of older adult support staff and the opportunities for their involvement by utilizing public funds and grants. Moreover, we are looking to expand not only to urban areas similar to Sendai City but also to underpopulated areas where the digital divide is even greater.4 As the program that we developed in this project could be described as an urban model that also incorporates support from university students, in future we plan to develop a model for training and dispatching older adult support staff that is tailored to the actual circumstances of small municipalities by collaborating with existing organizations in each region.

Conclusions

In this project, entities from industry, government, and academia worked closely together to promote the development and implementation of a digital skills learning ecosystem for older adults with the ultimate goal of bridging the digital divide. As a result, all of the KPIs that we initially set were achieved, and the outcomes exceeded our expectations. The project also succeeded in establishing a foundation for collaboration among industry, government, and academia to realize sustainable efforts even after its completion. In the future, we intend to leverage this foundation and continue our efforts to further bridge the digital divide.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Google.org for funding this project, and to the Japan Foundation for Aging and Health and its Evaluation Committee members for their continuous support and guidance throughout the project. We would like to express our sincere thanks to NTT Communications Corporation and Sendai City for their efforts in developing and implementing the "Manabiai" program as a collaborative project between industry, government and academia, and to the Smarties and Tohoku University students who participated in the program. We would also like to thank Dr. Taeko Makino for her efforts in conceiving and launching this project, and Risako Saito for her work as the secretariat.

References

- Kim HN, Freddolino PP, Greenhow C. Older adults' technology anxiety as a barrier to digital inclusion: a scoping review. Educational Gerontology. 2023;49(12):1021-1038.

- Ota Y, Saito M, Nakagomi A, Kondo K. Relationship of internet use to self-rated health and happiness among older people. Jpn J Geron. 2022;44(1):9-18.

- Lee OE, Kim DH. Bridging the digital divide for older adults via intergenerational mentor-up. Research on Social Work Practice. 2019;29(7):786-795.

- Onitsuka K, Hoshino S, Hashimoto S, Kuki Y. Causes of digital divide and possibility to improve such condition in hilly and mountainous areas. Jpn J Rural Plann. 2012;31(Special Issue):261-266.

Author

- Yasuyuki Taki

- Director, Smart Aging Research Center (SARC), Tohoku University

Professor, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer (IDAC), Tohoku University - Background

- 1993: Graduated from the Faculty of Science, Tohoku University, 1999: Graduated from the School of Medicine, Tohoku University, 2003: Ph.D. in Medicine, Tohoku University; appointed Medical Staff at Tohoku University Hospital, 2004: Assistant, IDAC, Tohoku University, 2007: Assistant Professor, Tohoku University Hospital, 2008: Associate Professor, IDAC, Tohoku University, 2012: Professor, Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization, Tohoku University, 2013-present: Professor, IDAC, Tohoku University, 2017: Deputy Director, SARC, Tohoku University, 2023-present: Director, SARC, Tohoku University

- Specialization:

- Brain development using large brain MRI databases, aging-related research